This story was originally published by ArtsATL.

The Black potters of Old Edgefield, South Carolina, have been known to folklorists, regional museums and collectors for more than a century. Now they have taken center stage in ”Hear Me Now: The Black Potters of Old Edgefield, South Carolina,” an exhilarating exhibition currently at the High Museum of Art through May 12. The exhibition is jointly organized by New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art and the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. Created by enslaved people from the 1830s through the Civil War, the clay vessels on display tell stories of artistry, resilience and subversion.

Until recently, these revelatory vessels were primarily categorized as material culture artifacts. The intensified interest in understanding the lived experiences of enslaved people in the United States, as well as admiration for the artistry of these objects, has ignited accelerated attention to Old Edgefield from curators, scholars and artists. In other words, this is an art, history and social justice exhibition all in one, heightened by the inclusion of contemporary artists.

Old Edgefield, South Carolina, a region encompassing Aiken, Edgefield, Greenfield, McCormick and Saluda counties today, was an “industrial slavery” production center for vessels made from the abundant local kaolin clay. Thousands of pots, both thrown and hand-built, were produced by highly skilled enslaved people. The pots, glazed with distinctive alkaline glazes and fired in wood kilns, were functional and primarily meant to store food or to serve as watercoolers. They were distributed throughout the South and beyond.

By definition of the circumstances in which they were made, the majority of this stoneware was created by uncredited makers. The anonymous potters often embellished their pots with highly accomplished designs that recall English slipware — not surprising considering the dominant White culture that controlled the industry. Some surviving examples have further embellishments including Black figurative scenes that may provide clues to the lived experience of enslaved people.

Credit: © 2022 Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

Credit: © 2022 Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

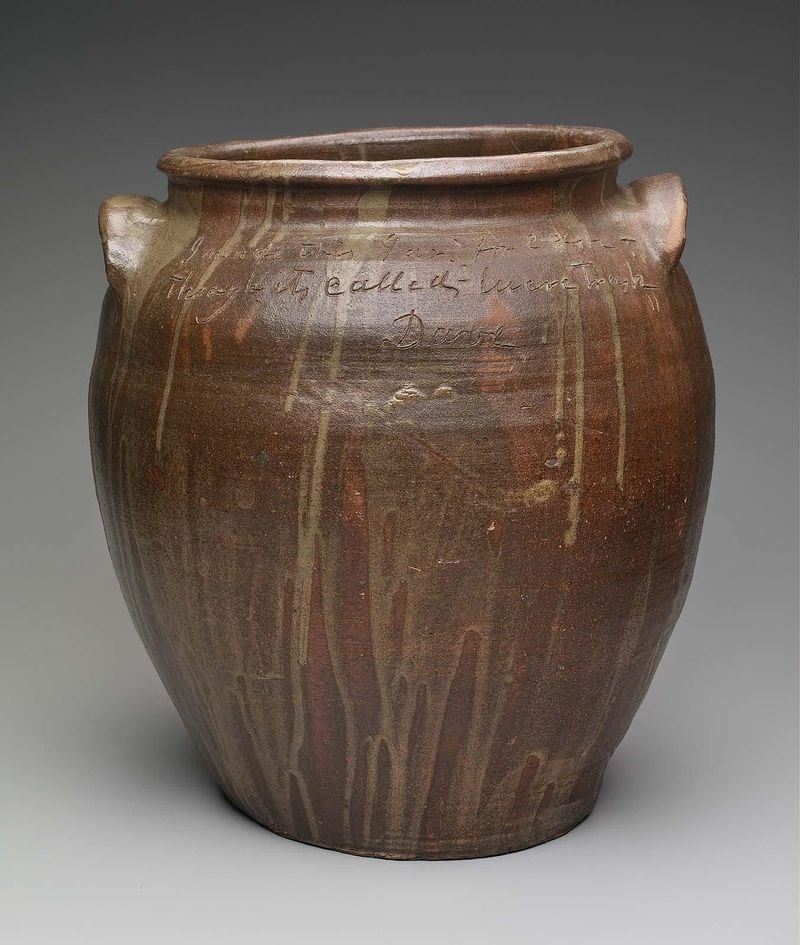

One master potter — David Drake — has a different story and is represented in the exhibition by 10 monumental vessels, including one from the High Museum’s collection. Probably born in 1801 to an enslaved mother, Drake is thought to have learned to read and write while working in a print shop before being sold to work in Drake & Rhodes Factory and then Stony Bluff Manufactory.

Drake was literate — explicitly a crime for enslaved people in the pre-Civil War South. Despite this, he often inscribed his largest vessels with his name, date, poems and observations. One telling poem is “I wonder where all my relation/Friendship to all — and every nation/LM Aug 16. 1857, Dave.” His poem jars were acts of resistance and empowerment, which he may have paid dearly for with a severely injured leg that could have been punishment for his audacity. Nonetheless, the factories greatly profited from the work of “Dave the Potter” or pejoratively as “Dave the Slave,” as he was marketed.

Distinctive from the functional jars and vessels created in the Edgefield factories are a selection of extraordinary face vessels from the 1850s. Made by the Edgefield potters for their own use, they are testaments to the makers’ creativity. The emergence of these face jugs coincided with the 1858 arrival of the Wanderer, a slave ship from Africa that landed in the United States 50 years after the transatlantic slave trade was made illegal. One hundred of these captives were sent to Edgefield. Scholars speculate these new arrivals, who were familiar with kaolin clay from West and Central Africa, may have triggered embedded memories within the culture of enslaved people of the African diaspora. The result is a compendium of face jugs echoing African forms, including nkisi nkondi power figures from Central Africa, one of which is included in the exhibition.

Credit: Photo © Woody De Othello.

Credit: Photo © Woody De Othello.

Bringing the exhibition full circle, the curators have included contemporary artists who have strong affinities with the Old Edgefield potters. In 2010, Theaster Gates explored the life, work and legacy of David Drake with his project “To Speculate Darkly: Theaster Gates and Dave the Potter,” which introduced Drake to many contemporary Black artists. The current exhibition only teases us with Gates’ small 2020 “Signature Study.” I would have liked to know more about Gates’ dive into Drake’s legacy. More successful in making their points are monumental clay sculptures by Simone Leigh, which reference both Old Edgefield and Nigerian clay pottery, and vessels by Adebunmi Gbadebo and Woody de Othello.

Credit: Photo by Victor Cocker Photography

Credit: Photo by Victor Cocker Photography

The exhibition also acknowledges the pottery traditions of the indigenous people that preceded the arrival of both Whites and enslaved Blacks with a 16th-century Woodland culture bowl and a jug from 2000 by Earl Robbins of the Catawba Indian Nation. Enhancing the Atlanta installation are works from the High Museum’s Southern decorative arts and folk art collections, which further contextualize the Edgefield jars. From a large Gullah sweetgrass tray to an intricate sideboard to a magnificent quilt embellished with snakes, these objects echo the experiences of enslaved people and their cultural memories.

Co-curator Jason R. Young of the University of Michigan eloquently ends his catalog essay with a reference to the 1895 poem “We Wear the Mask” by Paul Laurence Dunbar from which the exhibition title “Hear Me Now” is excerpted. Young states: “I find myself ever straining to hear what stories [the Edgefield potters] have to tell me, squinting to catch a glint of their hidden meanings.”

ART REVIEW

“Hear Me Now: The Black Potters of Old Edgefield, South Carolina”

Through May 12 at High Museum of Art. 10 a.m.-5 p.m. Tuesdays-Saturdays; noon to 5 p.m. Sundays. $18.50. 1280 Peachtree St. NE, Atlanta. 404-733-4400, high.org.

::

Louise E. Shaw has been a cultural worker in Atlanta for over 40 years. She served as executive director of Nexus Contemporary Art Center from 1983 to 1998 and was on Eyedrum’s ad hoc advisory board in the 2000s.

Credit: ArtsATL

Credit: ArtsATL

MEET OUR PARTNER

ArtsATL (artsatl.org) is a nonprofit organization that plays a critical role in educating and informing audiences about metro Atlanta’s arts and culture. ArtsATL, founded in 2009, helps build a sustainable arts community contributing to the economic and cultural health of the city.

If you have any questions about this partnership or others, please contact Senior Manager of Partnerships Nicole Williams at nicole.williams@ajc.com.